At-a-glance

- Microgrids provide less than 0.2 percent of U.S. electricity, but their capacity is expected to more than double in the next three years.

- Of the 160 microgrids in the United States, most are concentrated in seven states: Alaska, California, Georgia, Maryland, New York, Oklahoma, and Texas.

- Interest in microgrids is growing because of their ability to incorporate renewable energy sources and sustain electricity service during natural disasters.

- To increase deployment, a clear legal framework is needed to define a microgrid and set forth the rights and obligations of the microgrid owner with respect to customers and the larger utility grid operator.

What is a Microgrid?

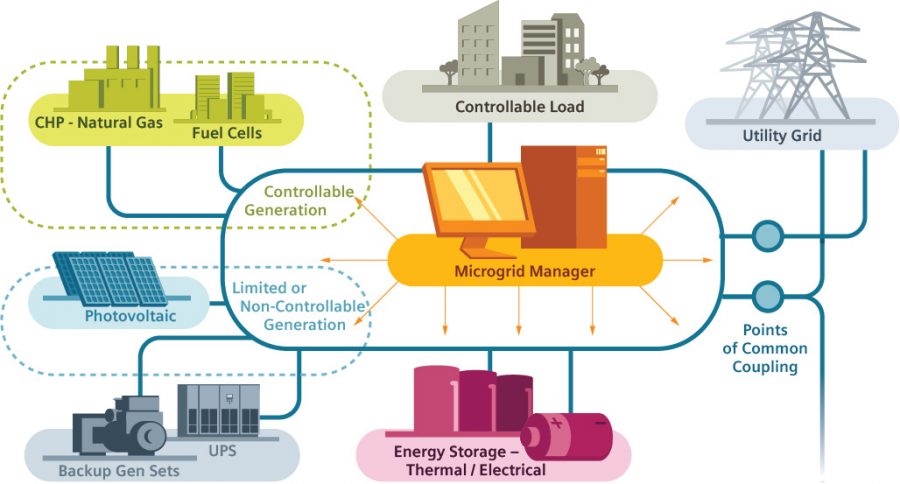

Microgrids are relatively small, controllable power systems composed of one or more generation units connected to nearby users that can be operated with, or independently from, the local bulk (i.e. high-voltage) transmission system, sometimes referred to as the “macrogrid.” Since the energy (power and heat) are created close to where they are used, microgrids are a form of distributed generation.

Historically, microgrids generated power using fossil fuel-fired combined heat and power (CHP) and reciprocating engine generators. Today, however, projects are increasingly leveraging more sustainable resources like solar power and energy storage. Microgrids can run on renewables, natural gas-fueled combustion turbines, or emerging sources such as fuel cells or even small modular nuclear reactors, when they become commercially available.

They can power critical facilities after a weather- or security-related outage affects the broader grid. Microgrids can also be the main electricity source for a hospital, university, or neighborhood. While single-user and campus microgrids, such as those that serve an industrial site or military base, have existed for decades, many cities are now interested in systems that can better integrate generation resources and load, serve multiple users, and/or meet environmental or emergency response objectives.

Several variations (and combinations) of microgrids are possible:

- Number of customers: Microgrids can serve a single building, multiple customers in a limited geographic area, or customers across an entire community. Microgrids commonly range in size from 100 kilowatts (kW) to multiple megawatts (MW).

- Load types and functions: A general purpose microgrid provides or supplements the services customers might otherwise receive from the macrogrid. A “community microgrid” serves a public purpose, such as powering police and fire stations, cell towers, and pumping city water and wastewater during emergencies. Community microgrids can also serve general purpose needs by providing power to displace or supplement service from the macrogrid on a day-to-day basis.

- Connection type: An off-grid system does not connect to the macrogrid and thus must be a sufficient power source for its customer. A microgrid connected to a macrogrid has greater flexibility since the macrogrid functions as an additional resource.

Microgrids provide a tiny fraction of U.S. electricity. In 2016, the United States had about 1.6 gigawatts (GW) of installed microgrid capacity out of 1,066 GW total capacity. That is expected to increase to 4.3 GW by 2020. Most microgrid projects are in Alaska, California, Georgia, Maryland, New York, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Microgrids are attractive to many large U.S. companies committed to working on their own and in partnership with governments to transition to a sustainable low-carbon economy. For example, NRG Energy, one of the country’s largest independent power producers, has turned its Princeton, New Jersey, headquarters into a fully-islandable microgrid demonstration project laboratory from which the company can test ideas for real-world applications. NRG is also collaborating with grid operator PJM to explore ways that microgrids can help enhance macrogrid operations.

Example of a Microgrid

No comments:

Post a Comment